Здравствуй.

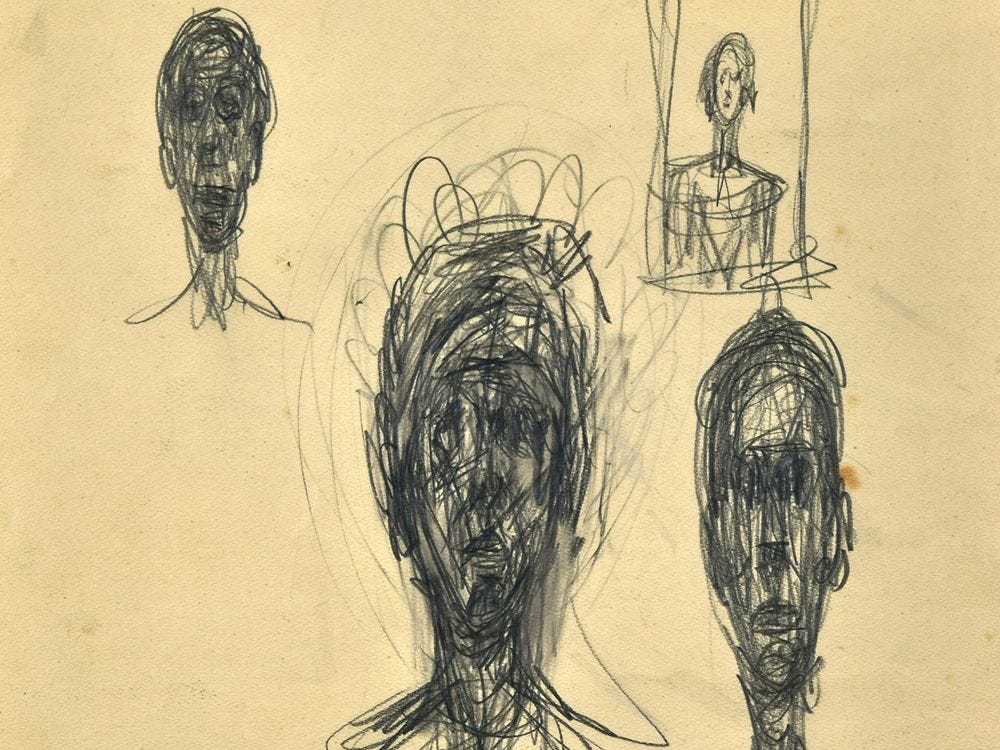

Недавно прочитала интервью, в котором затронули тему сострадания1 у Достоевского.

В подготовительных материалах к роману «Преступление и наказание» Фёдор Михайлович сделал такую запись: «Нет счастья в комфорте, (1)покупается счастье страданием». Самое христианское высказывание.

(1)‘покупается счастье страданием’ — could you tell me what case is used here amongst all 6 in the Russian case system? Right away! :)

Cases are for nouns. What nouns are used here? “Счастье” и ‘‘Страданием’’.

What is the main subject? We have to seek a noun in Nominative case.

Что? ‘‘Счастье’’. Что оно делает(ся)?

‘‘-СЯ’’ is a particle which emphasizes that a verb is reflexive.

Something is doing for happiness by something else.

‘‘Покупать’’ is a transitive verb2. Transitive verb means that its activity passes down to an object. Making it plain, suffer buys happiness. However here we notice that a better translation into English should include a passive voice: happiness is bought by suffering. Why? Because in Russian you see “страдание” is in Instrumental case (покупается чем? страданием)3. Let’s move on!

Он говорит: «Человек любит считать свои беды4, но не считает своих радостей».

‘считать беды’ is another example of transitive vebrs.

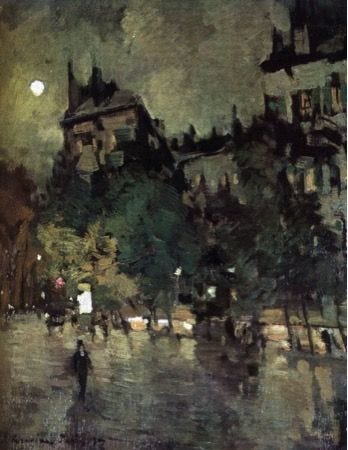

У Фёдора Михайловича после участия в кружке петрашевцев была показательная казнь5 на Сенатской площади. Его приговорили к смертной казни6 через расстреляние. Она (2)чуть было не совершилась. Он получает четыре года каторги; и потом четыре года в рядовых. На каторге он написал замечательную повесть «Записки из мёртвого дома7». Там описана жизнь изнутри8, как не сломаться. Это на все времена.

(2) чуть было не + verb in past tense — read an excellent explanation for use here.

Он нам чуть было весь перемёт колесами не покалечил.

Я чуть было не рассмеялась… I were almost

Give it a try and make up your sentence.

Там описана жизнь изнутри, как не сломаться. —

The life is described from within, how not to break down.

Фёдор Михайлович пишет: везде можно поставить себя с достоинством. Люди и тут, и там, главное постараться остаться человеком9. Своему брату Михаилу он написал, что (3)не выдержит и четырёх дней в бараке. А через три года напишет: «Человек есть существо ко всему привыкающее». (4)Он всё может пережить, когда есть цель, смысл и стремление.

(3) не выдержит…. will not stand… after nouns in Genitive case.

(4) Give your translation in the comment section. Let me see your vision of this sentence.

У Фёдора Михайловича есть замечательная мысль, которая на все времена10: главные вещи в жизни — это не вещи. И тот, кто это понимает, уже становится на путь спасения, на путь христианский. Кто-то сказал, что если ваши цели и планы не простираются дальше11 вашей смерти, тогда все ваши планы, стремления, мечты обрушатся12 со смертью. Только христианская вера, жизнь по вере простираются дальше смерти. Человек, живущий без Бога, — живой мертвец13, (5)живущий без цели и без смысла. Человек верующий и по(сле) смерти будет живым. Кстати, у Фёдора Михайловича есть потрясающая мысль: жизнь без веры в бессмертие собственной души и жизнь будущего века — (6)бессмысленна, бесцельна, невыносима и пуста.

(5) живущий — a present participle

= жить + ущ + ий

infinitive + suffix (the verb is in the 1st conjugation group) + male ending

(6) the prefix бес- (not без-) you see when the next is a quiet sound such as [к], [п], [с], [т], [ф], [х], [ц], [ч], [ш], [щ]. By the way, do you see now their meanings?14

Once again, read the final sentences in the final two excerpts:

Он <человек> всё может пережить, когда есть цель, смысл и стремление.

And

…жизнь без веры в бессмертие собственной души и жизнь будущего века — бессмысленна, бесцельна, невыносима и пуста.

And you, what do you think about these ideas?

Perhaps, that is the reason why we try to grant more our reading time to Dostoevsky: the contemporary society is tightly intertwined with meretricious stuff and money-based relations, whereas the writer says we have to seek joy in the little things. Today the little things are face-to-face conversations at the tea table when a good companion and quietness are much needed in this utterly noisy environment. In his каторга15 he had people and the Gospels, and yet he found happiness and the following steps in life were made for people’s sake. Everything comes because you started feeling\having one’s back. There is no fear if there is at least one supporting you in trouble. The rest will come. That is why we have to forgive Raskolnikov; that is why we have to pity Smerdyakov. Фёдор Михайлович tried to show us the real meaning of life inherent in Christianity — love.

It takes courage to admit. If one cannot love, no happiness shall one expect in the future.

Coming back to the newsletter’s title, I just want to leave you with a thought on why routine kills us:

<…> dance, as opposed to walking, cannot be explained in its utilitarian sense —dancing is a totally useless action, a (negative) reaction to the positivity of walking. And as B.-C. Han argues, it is dance, like art, one of the exclusively human activities — “only human beings can dance.”

What makes our life decrease a level of monotoneity? Human interaction.

Today’s letter is quite long but… now you know the reason.

Хороших выходных!

NB. The excerpts I carefully took from the interview posted here. The other day I studied some bits of Dostoevsky’s novels, and found out that in Russia there is an archimandrite considered as one of the best scholars on the writer’s life and bibliography living in Moscow but very tightly connected to Optina monastery16.

notice the prefix and the root in this word. ‘страдать с кем-то’… ‘suffer together’… ‘compassion’.

It’s my favourite word in Russian which means one ‘shares in bearing suffer’ of another. I may sound as an ignorant now but I surmise it’s one and most distinctive Russian character trait.

a verb combined with a noun or pronoun without any preposition in Acusative case: пишу письмо, строю дом. Read the full explanation here to get the sense.

troubles

a public execution

capital punishment in Dative case — it is what was given to FMD.

from within; from the inside

the main thing is to remain human

for all seasons; for all times. Two times it was used in today’s newsletter. Have you noticed it, right?

do not extend beyond <your death>

<they> will befall

living dead

meaningless, aimless

penal labour

a significant place in Dostoevsky’s life. One day I get my hands on writing about summer which turned out as a cornerstone for the rest life of Dostoevsky.

It is so useful to have the grammar slotted in just when I'm thinking 'what's going on here?'